Nineteenth Century Tour

Come learn about Hamilton’s 19th century Industrial Revolution by visiting the sites of some of the city’s first factories and workshops. Let this website be your guide as you walk the narrow corridor between the harbour and downtown, where the city’s first round of industrialization took place.

In the second half of the 19th century, Hamilton was transformed from a commercial centre with a sprinkling of small artisan shops into Canada’s pre-eminent industrial city. These changes did not occur overnight. The city’s first round of industrialization was an uneven process that took decades to unfold. This tour tells the story of the making of the 19th century industrial city.

Small manufacturers appeared in Hamilton as early as the 1830s, attracted by the city’s extensive hinterland markets, stretching from London to Guelph. The opening of a canal through the sand bar separating Lake Ontario from Burlington Bay in 1827 put Hamilton in an advantageous position at the head of Lake Ontario, giving access to raw materials and technology from the larger manufacturing centres to the east along the St. Lawrence and Erie canal systems.

By the 1840s, the city had developed a reputation as a regional metal centre. Its fledgling foundries turned out stoves, farming equipment and other necessities for settlers on the agricultural frontier. Production was done mostly in small shops by artisans using traditional handicraft techniques.

Read more +

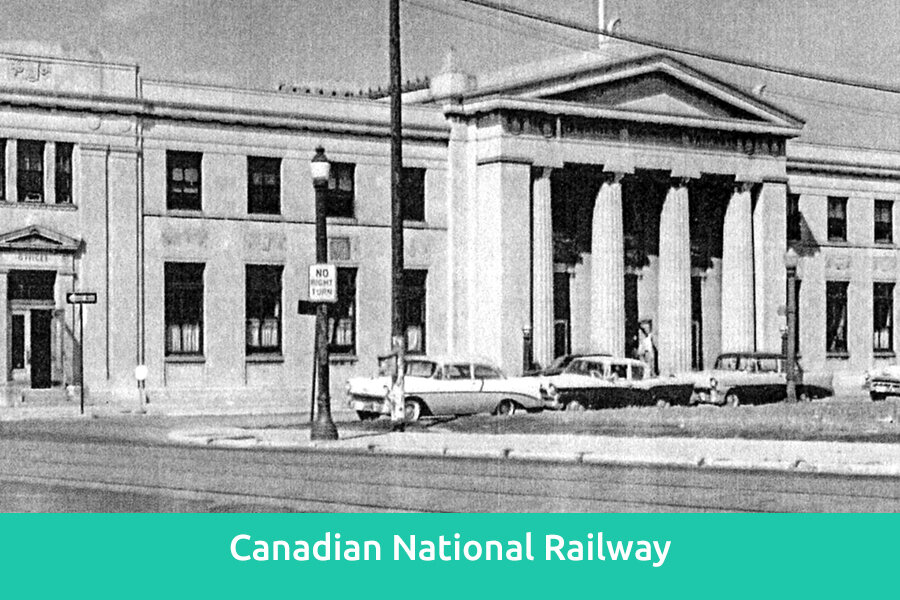

The arrival of the Great Western Railway in 1854 opened up vast new markets and attracted more industry to the city. By the 1860s, the city’s diverse industries included a large clothing factory, a boot and shoe enterprise, cigar and tobacco plants, steam engine and boiler works, sewing machine factories, stove foundries and many others.

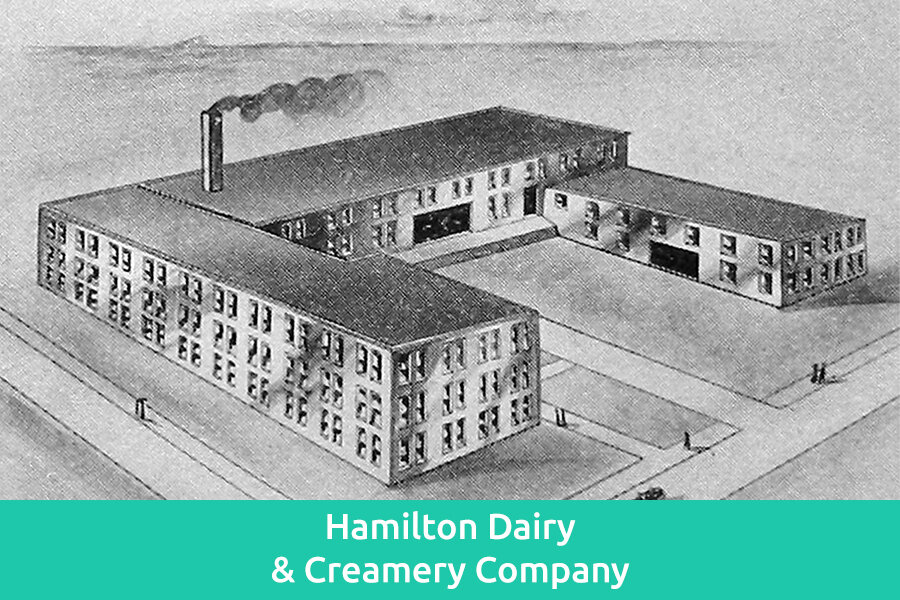

Most of Hamilton’s industrialists in the 1870s had started out in business as artisans, expanding their small shops as demand increased. Increasingly, they turned to steam engines to drive machinery through an elaborate system of belts, pulleys, wheels and shafting in their enlarged plants.

These modern “manufactories” were still a far cry from the automated plants of the 20th century. While steam-powered machinery replaced human muscle-power and skill in some cases, it sometimes simply allowed craftsworkers to perform traditional tasks with greater precision and ease. New mechanized work processes also created new groups of skilled workers: locomotive engineers, clothing cutters, and machinists, for example. Sometimes they had little or no impact on production. Moulders in Hamilton’s foundries, for example, relied on old-fashioned hand production techniques until after 1900.